Blog

“Do Midterm Elections Move Markets?“

I’m certainly ready to stop receiving political mail and seeing ads and campaigns everywhere I turn online. Thankfully, by the time you are reading this week’s blog, most of the mid-term election questions will have been answered, but I thought providing some historical context around midterm elections would be helpful. In a year when soaring inflation, the Russia and Ukraine war, and a bear market have dominated headlines, it’s important to remember how impactful and consequential this mid-term election could be. So, while control of Congress will likely be changing, do midterm elections actually have an effect on the stock market?

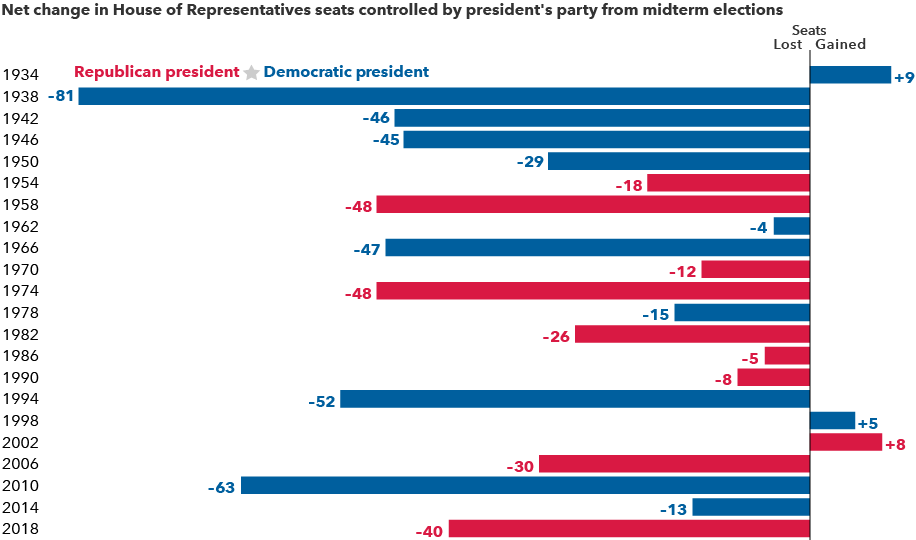

The Presidential Party Typically Loses Seats

Source: The American Presidency Project, “Seats in Congress Gained/Lost by the President’s Party in Mid-Term Elections.”

Midterm elections occur at the midpoint of a presidential term and usually result in the president’s party losing ground in Congress. Over the past 22 midterm elections, the president’s party has lost an average 28 seats in the House of Representatives and four in the Senate. Only twice has the president’s party gained seats in both chambers.

Why is this usually the case? First, supporters of the party not in power usually are more motivated to boost voter turnout. Also, the president’s approval rating typically dips during the first two years in office, which can influence swing voters and frustrated constituents.

“The Senate remains a toss-up, but history suggests we will see a backlash against the party in power that will result in Republicans taking back control of the House,” Miller says. “As far as investors are concerned that would end any chance for ambitious Democratic legislation the next two years.”

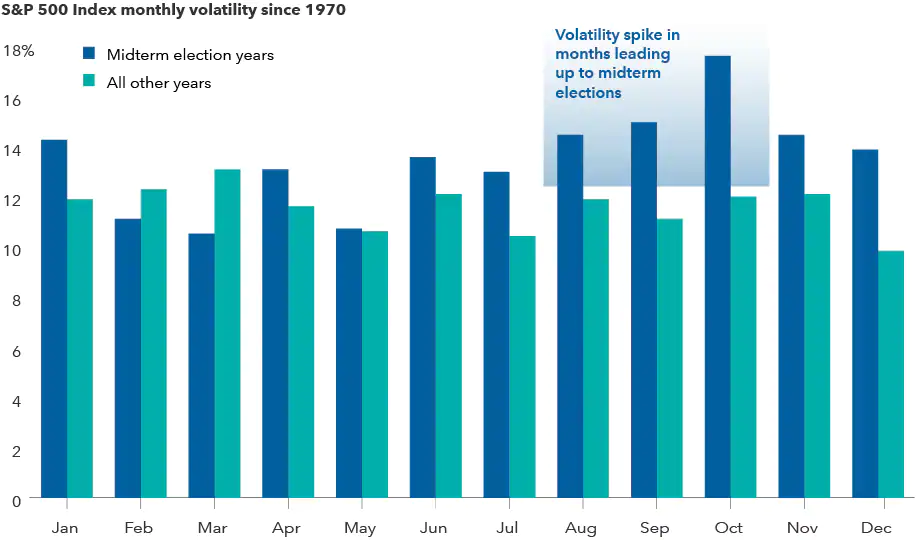

Midterm Election Years Have had Higher Volatility

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor’s. As of 12/31/21. Volatility is calculated using the standard deviation of daily returns for each individual month. Standard deviation is a measure of how returns over time have varied from the average. A lower number signifies lower volatility. The chart shows median volatility for the S&P 500 Index for each month since 1970, displayed on an annualized basis.

Elections can be tough on the nerves. Candidates often draw attention to the country’s problems, and campaigns regularly amplify negative messages. Policy proposals may be unclear and often target specific industries or companies.

It may come as no surprise then that market volatility is higher in midterm election years, especially in the weeks leading up to Election Day. Since 1970, midterm years have a median standard deviation of returns of nearly 16%, compared with 13% in all other years.

“I don’t think this election will be any different,” says equity portfolio manager Chris Buchbinder. “There may be bumps in the road, and investors should brace for short-term volatility, but I don’t expect the election results to be a huge driver of investment outcomes one way or the other.”

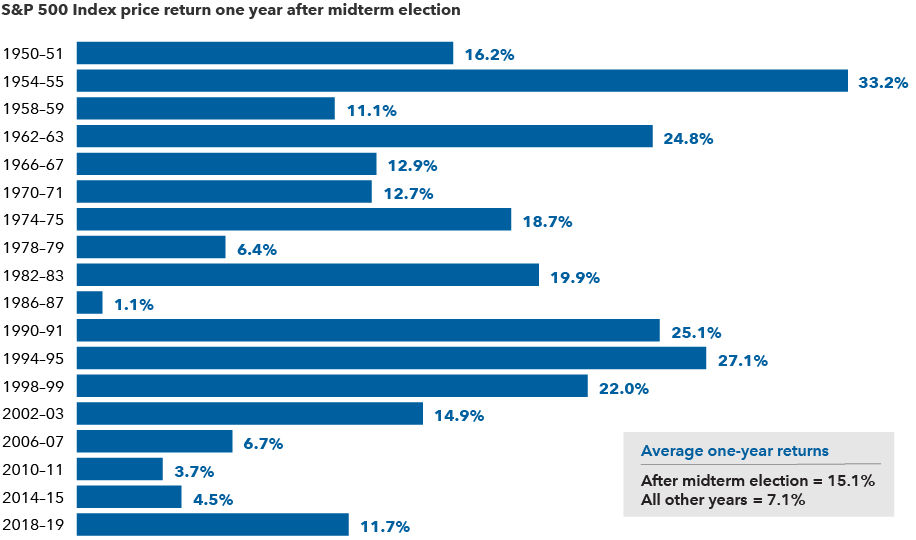

Market Returns After Mid-Term Elections Have Been Strong

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor’s. Calculations use Election Day as the starting date in all election years and November 5th as a proxy for the starting date in other years. Only midterm election years are shown in the chart. As of 12/31/21.

The silver lining for investors is that markets have tended to rebound strongly in subsequent months, and the rally that has often started shortly before Election Day hasn’t been just a short-term blip. Above-average returns have been typical for the full year following the election cycle. Since 1950, the average one-year return following a midterm election was 15%. That’s more than twice the return of all other years during a similar period.

Of course, every cycle is different, and elections are just one of many factors influencing market returns. For example, over the next year investors will need to weigh the impacts of a potential U.S. recession and global economic and geopolitical concerns.

Midterm elections — and politics as a whole — generate a lot of noise and uncertainty.

Even if elections spur higher volatility there is no need to fear them. The reality is that long-term equity returns come from the value of individual companies over time. Smart investors would be wise to look past the short-term highs and lows and maintain a long-term focus.